Difference between revisions of "Fundamental Interactions"

| (360 intermediate revisions by 21 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | * [[Fundamental Interactions Group|People and activities]] (← link to current activities and more information on members of the institute with research in Fundamental Interactions, of which the following provides some basic overview) |

||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- Our specializations: |

||

| + | |||

| + | * String theory ([http://hep.itp.tuwien.ac.at/string String Theory Group Webpage]) |

||

| + | * Strong Interactions, Quark-Gluon-Plasma ([http://hep.itp.tuwien.ac.at/~ipp Ipp], [[Kraemmer]], [[Rebhan]], [[Homepage_Andreas_Schmitt|Schmitt]]) |

||

| + | * Gravitation (Balasin, [http://quark.itp.tuwien.ac.at/~grumil/ Grumiller] - [http://quark.itp.tuwien.ac.at/~grumil/jobs.html START project]) |

||

| + | * Quantum Field Theory and noncommutative geometry (Schweda) --> |

||

| + | |||

According to our present knowledge there are four fundamental interactions in nature: gravity, electromagnetism, weak and strong interaction with electromagnetism and weak interaction unified in the electroweak theory. Gravity as well as electromagnetism are macroscopic phenomena, immediately present in our everyday life, like falling objects and static electricity. Weak and strong nuclear interactions, on the other hand, become only important on the microscopic, atomic and subatomic level. |

According to our present knowledge there are four fundamental interactions in nature: gravity, electromagnetism, weak and strong interaction with electromagnetism and weak interaction unified in the electroweak theory. Gravity as well as electromagnetism are macroscopic phenomena, immediately present in our everyday life, like falling objects and static electricity. Weak and strong nuclear interactions, on the other hand, become only important on the microscopic, atomic and subatomic level. |

||

The most important aspect of the strong interaction is that it provides stability to the nucleus overcoming electric repulsion, whereas the transmutation of neutrons into protons is the most well-known weak phenomenon. The aim of fundamental physics may be described as obtaining a deeper understanding of these interactions, and penultimately finding a unified framework, which understands the different interactions as different aspects of a single truly fundamental interaction. |

The most important aspect of the strong interaction is that it provides stability to the nucleus overcoming electric repulsion, whereas the transmutation of neutrons into protons is the most well-known weak phenomenon. The aim of fundamental physics may be described as obtaining a deeper understanding of these interactions, and penultimately finding a unified framework, which understands the different interactions as different aspects of a single truly fundamental interaction. |

||

| + | <!-- [[http://quark.itp.tuwien.ac.at/~grumil/pdf/Bachelor_2013.pdf Possible topics for a Bachelor thesis]] --> |

||

| − | == Research topics == |

||

| − | + | == Quantum field theory == |

|

| − | Describing the interactions on a more fundamental level the concepts of relativistic quantum field theories are employed. With the advent of quantum mechanics in the first decades of the 20th century it was realized that the electromagnetic field, including light, is quantized and can be seen as a stream of particles, the photons. This implies that the interaction between matter is mediated by the exchange of photons. |

+ | Describing the interactions on a more fundamental level the concepts of relativistic quantum field theories are employed. With the advent of quantum mechanics in the first decades of the 20th century it was realized that the electromagnetic field, including light, is quantized and can be seen as a stream of particles, the photons. This implies that the interaction between matter is mediated by the exchange of photons. In turn, matter particles are excitations of further quantum fields which pervade all of spacetime and which produce incessant vacuum fluctuations. |

| + | An example of a pure quantum field theoretical phenomenon is the scattering of light by light, which is impossible in the classical theory of electromagnetism. Quantum fluctuations can turn photons fleetingly into electron-positron pairs which can be exchanged with those of other photons. Light-by-light scattering has only recently been observed directly (in ultrarelativistic heavy-ion collisions at CERN), but it also contributes indirectly to other quantum field theoretical phenomena, in particular to the anomalous magnetic moment of elementary particles. The latter can be measured to such high accuracy that it can be used to test the limits of the present Standard Model of particle physics, because even particles that are much too heavy to be produced in present-day particle colliders make their appearance in vacuum fluctuations. |

||

| − | [[image:Loop.jpg|Full propagator of free propagation]] <br /> |

||

| − | Fig.: Full propagator in terms of free propagation and self-energy corrections. |

||

| + | [[image:Lbl.jpg|150px]] [[image:Lblg-2.jpg|200px]] <br /> |

||

| − | The construction of the perturbative NCQFT leads to new types of infrared (IR) singularities which represent a severe obstacle for the renormalization program at higher order and therefore lead to inconsistencies. The IR singularities are produced by the so-called UV finite nonplanar one-loop graphs (which are expected to be UV divergent by naive power counting) in U(N) gauge models and also in scalar field theories. The interplay between expected UV divergencies and the existence of the IR singularities is the so-called UV/IR mixing problem of NCQFT. One also has to stress that the usual UV divergences may be removed by the standard renormalization procedure. |

||

| + | Fig.: Light-by-light scattering (photons respresented by wavy lines, charged particles by lines with arrows), and virtual light-by-light scattering in higher-order corrections to the anomalous magnetic moment of charged particles. |

||

| + | Recent research topics at our institute include hadronic light-by-light scattering where the photon couples to strongly interacting particles. The interactions of the latter are too complex to be captured by perturbation theory and Feynman diagrams, requiring new techniques such as gauge-gravity correspondence. The latter is also known as holography, because it is based on the description of a strongly interacting quantum field theory in flat spacetime as sort of a hologram in a higher-dimensional curved spacetime. |

||

| − | The present research activities are devoted to find solutions for the UV/IR mixing problem of noncommutative gauge field models. In order to respect the effects of noncommutativity implied by the non-abelian structure a consistent treatment requires the use of the BRS quantization procedure even for a U(1) deformed Maxwell theory. |

||

| + | A theoretically clean and well studied example of gauge-gravity duality is the so-called AdS/CFT correspondence, where the higher dimensional spacetime is a maximally symmetric negatively curved (anti de Sitter) space and the quantum field theory in one dimension less is a conformal field theory (CFT). Conformal field theories also play important roles in string theory (see below). |

||

| + | * Highlight: Our involvement in the [[Myon g-2|muon g-2]] (in German) |

||

| − | === Gravitation === |

||

| + | |||

| + | <!--The construction of the perturbative NCQFT leads to new types of infrared (IR) singularities which represent a severe obstacle for the renormalization program at higher order and therefore lead to inconsistencies. The IR singularities are produced by the so-called UV finite nonplanar one-loop graphs (which are expected to be UV divergent by naive power counting) in U(N) gauge models and also in scalar field theories. The interplay between expected UV divergencies and the existence of the IR singularities is the so-called UV/IR mixing problem of NCQFT. One also has to stress that the usual UV divergences may be removed by the standard renormalization procedure. |

||

| + | |||

| + | The present research activities are devoted to find solutions for the UV/IR mixing problem of noncommutative gauge field models. In order to respect the effects of noncommutativity implied by the non-abelian structure a consistent treatment requires the use of the BRS quantization procedure even for a U(1) deformed Maxwell theory.--> |

||

| + | |||

| + | == Gravitation == |

||

Since the groundbreaking work of Einstein, gravitation is conceived as defining the geometry of spacetime - even defining the very concepts of time and space itself. Planetary motion as well as the motion of massless particles, that is to say light, become the straightest possible paths in a non-Euclidean geometry. |

Since the groundbreaking work of Einstein, gravitation is conceived as defining the geometry of spacetime - even defining the very concepts of time and space itself. Planetary motion as well as the motion of massless particles, that is to say light, become the straightest possible paths in a non-Euclidean geometry. |

||

| Line 24: | Line 40: | ||

Fig.: Light-cone of an event representing its causal past and future. |

Fig.: Light-cone of an event representing its causal past and future. |

||

| − | General relativity is a very successful theory. Its predictions range from the deflection of light by massive bodies which distort spacetime (Einstein-lensing) to that of gravitational radiation carrying away energy in the form of "ripples" in spacetime (Hulse-Taylor binary pulsar), as well as to the expansion of the universe (microwave background radiation). |

+ | General relativity is a very successful theory. Its predictions range from the deflection of light by massive bodies which distort spacetime (Einstein-lensing) to that of gravitational radiation carrying away energy in the form of "ripples" in spacetime (Hulse-Taylor binary pulsar), as well as to the expansion of the universe (microwave background radiation). One of the most spectacular predictions of general relativity is the existence of black holes, which by now has been confirmed indirectly by numerous astrophysical observations. |

| + | Despite of these successes there are several unresolved problems in the physics of gravitation, some of which are considered as the biggest problems in contemporary theoretical physics: |

||

| − | Deeper insights into the structure of physical systems have often been achieved by the imposition of symmetries. This usually breaks the problem down into simpler building blocks which ideally allow a complete solution. Gravity is no exception to this rule since the prototypic black-hole solution, the Schwarzschild geometry (actually the first exact non-trivial solution of the Einstein-equations), has been found precisely along theses lines, i.e. upon imposing spherical symmetry. It is therefore natural to pursue a similar plan of attack for the quantization of gravity. The corresponding models become gravitational theories in a 1+1 dimensional spacetime coupled to the area of the two-sphere which becomes a dynamical variable in the reduced theory. |

||

| + | * The cosmological constant problem entails a gigantic discrepancy (123 orders of magnitude) between observation and naive theoretical expectation, and so far no satisfying explanation exists that resolves this discrepancy. |

||

| + | * Numerous astrophysical and cosmological observations reveal discrepancies with the theory of general relativity, unless we postulate the existence of dark matter, which so far has not been detected in particle physics experiments. |

||

| − | === Quark-Gluon plasma === |

||

| + | * The elusive theory of quantum gravity still is very much a theory under construction, with several conceptual and technical issues seeking for solutions. |

||

| − | Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the accepted theory of the strong interactions responsible for the binding of quarks into hadrons such as protons and neutrons, and the binding of protons and neutrons into atomic nuclei. The fundamental particles of QCD, the quarks and gluons, carry a new form of charge, which is called color because of its triplet nature in the case of the quarks (e.g. red, green, blue); gluons come in eight different colors which are composites of color and anticolor charges. However, quarks and gluons have never been observed as free particles. Nevertheless, because quarks have also electrical charge, they can literally be seen as constituents of hadrons by deep inelastic scattering using virtual photons. The higher the energy of the probing photon, the more do the quarks appear as particles propagating freely within a hadron. This feature is called "asymptotic freedom". It arises from so-called nonabelian gauge field dynamics, with gluons being the excitations of the nonabelian gauge fields similarly to photons being the excitations of the electromagnetic fields, except that gluons also carry color charges. Asymptotic freedom is well understood, and the Nobel prize was awarded to its main discoverers Gross, Politzer, and Wilczek in 2004. |

||

| + | * General relativity predicts its own failure as a consequence of the famous singularity theorems. Physically this means that spacetime contains regions where the curvature grows without a bound. The most prominent examples are the singularities within black holes as well as the Big Bang singularity. |

||

| − | Much less understood is the phenomenon of "confinement", which means that only color-neutral bound states of quarks and gluons exist. This confinement can in fact be broken in a medium if the density exceeds significantly that of nuclear matter. When hadrons overlap so strongly that they loose their individuality, quarks and gluons come into their own as the elementary degrees of freedom. It is conceivable that such conditions are realized in the cores of certain neutron stars. |

||

| + | Deeper insights into the structure of physical systems have often been achieved by the imposition of symmetries. This usually breaks the problem down into simpler building blocks which ideally allow a complete solution. Gravity is no exception to this rule since the prototypic black-hole solution, the Schwarzschild geometry (actually the first exact non-trivial solution of the Einstein-equations), has been found precisely along theses lines, i.e. upon imposing spherical symmetry. It is therefore natural to pursue a similar plan of attack for the quantization of gravity. The corresponding models become gravitational theories in a 1+1 dimensional spacetime coupled to the area of the two-sphere which becomes a dynamical variable in the reduced theory. There are several other ways how lowerdimensional (1+1 and 2+1) models arise from higherdimensional configurations in string theory or general relativity, and the description of gravity in lower dimensions is one of the key research fields of our group. |

||

| − | [[Image:Phase_diag03.jpg|phase diagram of quark-gluon matter]] <br /> |

||

| − | Fig.: Qualitative sketch of the phase diagram of quark-gluon matter as a function of temperature T and quark chemical potential µ. Solid lines denote rst-order phase transitions, the dashed line a rapid crossover. |

||

| + | == Quark-Gluon plasma == |

||

| − | At comparatively low temperatures, quark matter is known to form Cooper pairs and turns into a color superconductor. Also at temperatures just above the superconductivity phase new phenomena appear, which reflect that quark matter has strong deviations from an ideal Fermi liquid. In particular, there is anomalous behaviour in the low-temperature specific heat, which has been calculated for the first time systematically by our group. This has already found application in revised calculations of the cooling behavior of young neutron stars. |

||

| + | Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the accepted theory of the strong interactions responsible for the binding of quarks into hadrons such as protons and neutrons, and the binding of protons and neutrons into atomic nuclei. The fundamental particles of QCD, the quarks and gluons, carry a new form of charge, which is called color because of its triplet nature in the case of the quarks (e.g. red, green, blue); gluons come in eight different colors which are composites of color and anticolor charges. However, quarks and gluons have never been observed as free particles. Nevertheless, because quarks have also electrical charge, they can literally be seen as constituents of hadrons by deep inelastic scattering using virtual photons. The higher the energy of the probing photon, the more do the quarks appear as particles propagating freely within a hadron. This feature is called "asymptotic freedom". It arises from so-called nonabelian gauge field dynamics, with gluons being the excitations of the nonabelian gauge fields similarly to photons being the excitations of the electromagnetic fields, except that gluons also carry color charges. Asymptotic freedom is well understood, and the Nobel prize was awarded to its main discoverers Gross, Politzer, and Wilczek in 2004. |

||

| − | === String theory === |

||

| + | Much less understood is the phenomenon of "confinement", which means that only color-neutral bound states of quarks and gluons can be observed. This confinement can be overcome when the temperature is very large, as, for example, in the first instances of the Early Universe. In this case, quarks and gluons form a quantum fluid that is known as the quark-gluon plasma. Its unique properties are studied on Earth in large collider facilities at LHC (CERN, Switzerland) or at RHIC (BNL, United States), where this plasma is created in ultrarelativistic heavy-ion collision experiments. |

||

| − | The names of the fundamental forces are related to their strength. The strong force is much stronger than electromagnetism and is thus able to overcome the repulsive force between objects with the same electrical charge (protons or quarks). The weak force is weaker than electromagnetism but still much stronger than gravity. The reason that we almost only recognize gravity in everyday life is that the macroscopic objects are neutral. They don't carry an effective color charge and they carry - if at all - only very small electric charges. For gravity there is no negative charge (negative mass), so that all the small gravitational effects add up to something which is strong enough to move galaxies and build black holes. The seperate description of the forces is quite accurate by now. This is summarized in the standard model of particle physics. |

||

| + | <!-- --> |

||

| + | <!--Much less understood is the phenomenon of "confinement", which means that only color-neutral bound states of quarks and gluons exist. This confinement can in fact be broken in a medium if the density exceeds significantly that of nuclear matter. When hadrons overlap so strongly that they loose their individuality, quarks and gluons come into their own as the elementary degrees of freedom. It is conceivable that such conditions are realized in the cores of certain neutron stars.--> |

||

| − | There is only one particle (the Higgs boson), which is predicted by the standard model and has not yet been found. A measure for the strength of a force are the coupling constants of the corresponding theory. They are, however, not constant, but depend on the energy level one is dealing with. If one extrapolates their values to high energies, one discovers that the couplings of electromagnetism, strong and weak force meet at a certain energy level almost in one single point (see Figure 1). This supports the idea that those three forces could be just different aspects of one and the same universal force. There are several theories which try to describe this unification. They are called GUTs, 'grand unified theories'. However, to be really 'grand', such a unification should also include gravity, whose coupling constant is far weaker still at this high energies. The theory, which will manage to unify all forces, including gravity, is sometimes called TOE, "theory of everything". String theory is one candidate, and at present actually the only one for this TOE. |

||

| − | [[Image: |

+ | [[Image:Phase_diag03.jpg|phase diagram of quark-gluon matter]] <br /> |

| + | Fig.: Qualitative sketch of the expected phase diagram of quark-gluon matter as a function of temperature T and quark chemical potential µ. Solid lines denote first-order phase transitions, the dashed line a rapid crossover. |

||

| − | Fig.: Left: Point particle interaction, Right: Closed string interaction, note the smooth interaction surface. |

||

| + | In our group, we investigate different thermal and nonthermal properties of the quark-gluon plasma, putting particular emphasis on its non-equilibrium early-time evolution shortly after the heavy-ion collision. Using a variety of different techniques, involving perturbative calculations, kinetic theory, hydrodynamics, holography, real-time lattice simulations and artificial neural networks, not only enables us to extract dynamical and universal key features of the plasma, but also to link to other fields of research like machine learning, gravity, the Early Universe and experiments with ultra-cold Bose gases. |

||

| − | 'SUSY' stands for supersymmetry and means that there is an exchange symmetry between fermionic particles (like quarks and electrons) and bosonic ones (like photons and even gravitons, if one includes gravity into the considerations). It does, however, not relate the already known particles, but it predicts new supersymmetric partners to the known particles (called e.g. squarks, selectrons, photinos and gravitinos). So far none of those superparticles has been discovered, but there are a lot of theoretical reasons for believing in supersymmetry. Supersymmetry is an integral part of string theory, or more precisely 'superstring theory'. Within one year now, the new accelerator LHC (large hadron collider) at CERN will start and try to produce the Higgs boson and the superparticles mentioned above and will therefore also be a first test for string theory. |

||

| + | <!-- --> |

||

| + | <!--At comparatively low temperatures, quark matter is known to form Cooper pairs and turns into a color superconductor. Also at temperatures just above the superconductivity phase new phenomena appear, which reflect that quark matter has strong deviations from an ideal Fermi liquid. In particular, there is anomalous behaviour in the low-temperature specific heat, which has been calculated for the first time systematically by our group. This has already found application in revised calculations of the cooling behavior of young neutron stars.--> |

||

| − | For further information and news on fundamental physics visit: |

||

| + | == String theory == |

||

| − | <div style="position: relative">[[Image:whatsnew.gif]] |

||

| − | <div style="position: absolute; left: 0px; top: 5px"> |

||

| − | {| style="background:transparent; font-size:48px; font-color:white" |

||

| − | |- |

||

| − | |[http://teilchen.at _____] |

||

| − | |} |

||

| − | </div> |

||

| − | </div> |

||

| + | The names of the fundamental forces are related to their strength. The strong force is much stronger than electromagnetism and is thus able to overcome the repulsive force between objects with the same electrical charge (protons or quarks). The weak force is weaker than electromagnetism but still much stronger than gravity. The reason that we almost only recognize gravity in everyday life is that the macroscopic objects are neutral. They don't carry an effective color charge and they carry - if at all - only very small electric charges. For gravity there is no negative charge (negative mass), so that all the small gravitational effects add up to something which is strong enough to move galaxies and build black holes. The seperate description of the forces is quite accurate by now. This is summarized in the standard model of particle physics. |

||

| − | This contains the public outreach web pages of the [http://oepg-fakt.itp.tuwien.ac.at/fakt/ Fachausschuss für Kern- und Teilchenphysik (FAKT)] of the [http://www.oepg.at/ ÖPG] (Austrian Physical Society), which our institute are hosting. |

||

| + | A measure for the strength of a force are the coupling constants of the corresponding theory. They are, however, not constant, but depend on the energy level one is dealing with. If one extrapolates their values to high energies, one discovers that the couplings of electromagnetism, strong and weak force meet at a certain energy level almost in one single point (see Figure 1). This supports the idea that those three forces could be just different aspects of one and the same universal force. There are several theories which try to describe this unification. They are called GUTs, 'grand unified theories'. However, to be really 'grand', such a unification should also include gravity, whose coupling constant is far weaker still at this high energies. The theory, which will manage to unify all forces, including gravity, is sometimes called TOE, "theory of everything". String theory is one candidate, and at present actually the only one for this TOE. |

||

| + | [[Image:Particle_string_interaction.jpg| Point particle and closed string interaction]] <br /> |

||

| − | __NOEDITSECTION__ |

||

| + | Fig.: Left: Point particle interaction, Right: Closed string interaction, note the smooth interaction surface. |

||

| − | ---- |

||

| + | 'SUSY' stands for supersymmetry and means that there is an exchange symmetry between fermionic particles (like quarks and electrons) and bosonic ones (like photons and even gravitons, if one includes gravity into the considerations). It does, however, not relate the already known particles, but it predicts new supersymmetric partners to the known particles (called e.g. squarks, selectrons, photinos and gravitinos). So far none of those superparticles has been discovered, but there are a lot of theoretical reasons for believing in supersymmetry. Supersymmetry is an integral part of string theory, or more precisely 'superstring theory'. If supersymmetry is realized at energies not too far above the scale of electroweak symmetry breaking, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN may be able to discover its signatures in its ongoing searches of physics beyond the standard model. |

||

| − | == Preprints == |

||

| + | <!-- |

||

| − | Preprints of the group '''Fundamental Interactions''': |

||

| + | == Further Information == |

||

| + | * [https://owncloud.tuwien.ac.at/index.php/s/1kJ4NNZ6xJOz6q3 Presentation slides] for the course 138.039 - Introduction into the Fields of Science and Research of the Faculty of Physics |

||

| − | === Current year === |

||

| + | * [[Fundamental_Interactions_Preprints|(Some of) our preprints in the field of fundamental interactions]] (Complete lists of preprints and publications can now be found https://arxiv.org and https://inspirehep.net by searching by author) |

||

| + | --> |

||

| + | __NOEDITSECTION__ |

||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-01</b> A. Rebhan, P. van Nieuwenhuizen and R. Wimmer, ''Quantum corrections to solitons and BPS saturation'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0902.1904 hep-th/0902.1904] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-02</b> A. Rebhan, A. Schmitt and P. van Nieuwenhuizen, ''One-loop results for kink and domain wall profiles at zero and finite temperature'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0903.5242 hep-th/0903.5242] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-03</b> D. Grumiller and P. van Nieuwenhuizen, ''Holographic counterterms from supersymmetry without boundary conditions'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.3486 hep-th/0908.3486] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-04</b> M. Kreuzer, ''Heterotic (0,2) Gepner models and related geometries'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0903.nnnn hep-ph/0903.nnnn] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-05</b> M. Kreuzer, ''The making of Calabi-Yau spaces: Beyond toric hypersurfaces'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0903.nnnn hep-ph/0903.nnnn] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-06</b> P. M. Chesler, A. Gynther and A. Vuorinen, ''On the dispersion of fundamental particles in QCD and N=4 Super Yang-Mills theory'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0906.3052 hep-ph/0906.3052] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-07</b> M.E. Carrington and A. Rebhan, ''On the imaginary part of the next-to-leading order static gluon self-energy in an anisotropic non-Abelian plasma'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0906.5220 hep-ph/0906.5200] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-08</b> E. Avsar, E. Iancu, L. McLerran and D.N. Triantafyllopoulos, ''Shockwaves and deep inelastic scattering within the gauge/gravity duality'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0907.4604 hep-ph/0907.4604] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-09</b> M. Schimpf and R.C. Rashkov, ''A note on strings in deformed AdS_4 x CP3 background'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0908.2246 hep-th/0908.2246] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-10</b> H. Dimov, M. Michalcik and R.C. Rashkov, ''Strings in deformed T11: giant magnon and single spike solutions'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0908.3065 hep-th/0908.3065] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-11</b> H. Dimov and R.C. Rashkov, ''On the pulsating strings in AdS_4 x CP3'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0908.2218 hep-th/0908.2218] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-12</b> D. Grumiller and A.M. Piso, ''Exact relativistic viscous fluid solutions in near horizon extremal Kerr background'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0909.2041 astro-ph.SR/0909.2041] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-13</b> D. Grumiller and I. Sachs, ''AdS3/LCFT2 - Correlators in Cosmological Topologically Massive Gravity'' |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-14</b> A. Gynther, A. Kurkela and A.Vuorinen, ''The N_f^3 g^6 term in the pressure of hot QCD'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0909.3521 hep-ph/0909.3521] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-09-15</b> A. Rebhan, A. Schmitt and S. A. Stricker, ''Anomalies and the chiral magnetic effect in the Sakai-Sugimoto model'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0909.4782 hep-th/0909.4782] |

||

| − | |||

| − | === 2008 === |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-01</b> Ph. de Forcrand, A. Kurkela and A. Vuorinen, ''Center-Symmetric Effective Theory for High-Temperature SU(2) Yang-Mills Theory'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0801.1566 hep-ph/0801.1566] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-02</b> V. Braun, M. Kreuzer, B. A. Ovrut and E. Scheidegger, ''Worldsheet Instantons and Torsion Curves'', [http://arxiv.org/abs/0801.4154 hep-th/0801.4154] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-03</b> C. P. Herzog, S. A. Stricker and A. Vuorinen, ''Remarks on Heavy-Light Mesons from AdS/CFT'', [http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.2956 hep-th/0802.2956] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-04</b> V. Batyrev and M. Kreuzer, ''Constructing new Calabi-Yau 3-folds and their mirrors via conifold transitions'', [http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.3376 math/0802.3376] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-05</b> A. Rebhan, M. Strickland and M. Attems, ''Instabilities of an anisotropically expanding non-Abelian plasma: 1D+3V discretized hard-loop simulations'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0802.1714 hep-ph/0802.1714] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-06</b> A. Fotopoulos and M. Tsulaia, ''Gauge Invariant Lagrangians for Free and Interacting Higher Spin Fields. A Review of the BRST formulation.'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0805.1346 hep-th/0805.1346] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-07</b> M. G. Alford, M. Braby and A. Schmitt, ''Bulk viscosity in kaon-condensed color-flavor locked quark matter'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0806.0285 nucl-th/0806.0285] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-08</b> E. Kiritsis, A. Schellekens and M. Tsulaia, ''Discriminating MSSM families in (free-field) Gepner orientifolds'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0809.0083 hep-th/0809.0083] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-09</b> Changrim Ahn, P. Bozhilov and R.C. Rashkov, ''Neumann-Rosochatius integrable system for strings on AdS4 x CP3'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0807.3134 hep-th/0807.3134] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-10</b> R.C. Rashkov, ''A note on the reduction of the AdS4 x CP3 string model'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0808.3057 hep-th/0808.3057] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-11</b> M. Kreuzer, R.C. Rashkov and M. Schimpf, ''Near Flat Space limit of strings on AdS4 x CP3'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0810.2008 hep-th/0810.2008] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-12</b> H. Dimov, R.C. Rashkov, ''Pulsating strings on AdS4 x CP3'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0811.xxxx hep-th/0811.xxxx] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-13</b> H. Dimov, R.C. Rashkov, ''Multispin strings on AdS4 x CP3 I: giant magnon solutions'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0811.xxxx hep-th/0811.xxxx] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-14</b> M. Kreuzer, ''On the Statistics of Lattice Polytopes'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0809.1188 arXiv:0809.1188] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-15</b> A. Rebhan, '' Nonabelian plasma instabilities in Bjorken expansion'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0810.2805 hep-ph/0810.2805] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-16</b> A.M. Kasprzyk, M. Kreuzer, B. Nill, ''On the combinatorial classification of toric log del Pezzo surfaces'' [http://arxiv.org/abs/0810.2207 arXiv:0810.2207] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-17</b> A. Rebhan, ''Hard loop effective theory of the (anisotropic) quark gluon plasma'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0811.0457 hep-ph/0811.0457] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-18</b> M.E. Carrington and A. Rebhan, ''Next-to-leading order static gluon self-energy for anisotropic plasmas'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0810.4799 hep-ph/0810.4799] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-19</b> A. Rebhan, A. Schmitt and S. A. Stricker, ''Meson supercurrents and the Meissner effect in the Sakai-Sugimoto model'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0811.3533 hep-th/0811.3533] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-20</b> A. Collinucci, M. Kreuzer, C. Mayrhofer and N.-O. Walliser, ''Four-modulus "Swiss Cheese" chiral models'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0811.4599 hep-th/0811.4599] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-21</b> R.S. Garavuso, M. Kreuzer and A. Noll, ''Fano hypersurfaces and Calabi-Yau supermanifolds'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0812.0097 hep-th/0812.0097] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-22</b> A. Collinucci, ''New F-theory lifts'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0812.0175 hep-th/0812.0175] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-23</b> S. Beane, D.B. Kaplan and A. Vuorinen, ''Perturbative nuclear physics'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0812.3938 nucl-th/0812.3938] |

||

| − | |||

| − | * <b>TUW-08-24</b> A. Vuorinen, ''Equation of state of zero-temperature quark matter with finite quark masses'' [http://arXiv.org/abs/0810.3595 hep-ph/0810.3595] |

||

| − | |||

| − | === Previous years === |

||

| − | |||

| − | : [[Fundamental_Interactions_Preprints_2007|2007]], [[Fundamental_Interactions_Preprints_2006|2006]], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints05.html 2005], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints04.html 2004], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints03.html 2003], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints02.html 2002], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints01.html 2001], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints00.html 2000], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints99.html 1999], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints98.html 1998], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints97.html 1997], [http://tph.tuwien.ac.at/~moessmer/preprints96.html 1996] |

||

| − | |||

| − | For published articles, talks, and poster presentations see [[Publications]] |

||

Latest revision as of 09:41, 27 April 2021

- People and activities (← link to current activities and more information on members of the institute with research in Fundamental Interactions, of which the following provides some basic overview)

According to our present knowledge there are four fundamental interactions in nature: gravity, electromagnetism, weak and strong interaction with electromagnetism and weak interaction unified in the electroweak theory. Gravity as well as electromagnetism are macroscopic phenomena, immediately present in our everyday life, like falling objects and static electricity. Weak and strong nuclear interactions, on the other hand, become only important on the microscopic, atomic and subatomic level.

The most important aspect of the strong interaction is that it provides stability to the nucleus overcoming electric repulsion, whereas the transmutation of neutrons into protons is the most well-known weak phenomenon. The aim of fundamental physics may be described as obtaining a deeper understanding of these interactions, and penultimately finding a unified framework, which understands the different interactions as different aspects of a single truly fundamental interaction.

Quantum field theory

Describing the interactions on a more fundamental level the concepts of relativistic quantum field theories are employed. With the advent of quantum mechanics in the first decades of the 20th century it was realized that the electromagnetic field, including light, is quantized and can be seen as a stream of particles, the photons. This implies that the interaction between matter is mediated by the exchange of photons. In turn, matter particles are excitations of further quantum fields which pervade all of spacetime and which produce incessant vacuum fluctuations.

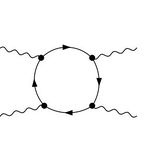

An example of a pure quantum field theoretical phenomenon is the scattering of light by light, which is impossible in the classical theory of electromagnetism. Quantum fluctuations can turn photons fleetingly into electron-positron pairs which can be exchanged with those of other photons. Light-by-light scattering has only recently been observed directly (in ultrarelativistic heavy-ion collisions at CERN), but it also contributes indirectly to other quantum field theoretical phenomena, in particular to the anomalous magnetic moment of elementary particles. The latter can be measured to such high accuracy that it can be used to test the limits of the present Standard Model of particle physics, because even particles that are much too heavy to be produced in present-day particle colliders make their appearance in vacuum fluctuations.

Fig.: Light-by-light scattering (photons respresented by wavy lines, charged particles by lines with arrows), and virtual light-by-light scattering in higher-order corrections to the anomalous magnetic moment of charged particles.

Recent research topics at our institute include hadronic light-by-light scattering where the photon couples to strongly interacting particles. The interactions of the latter are too complex to be captured by perturbation theory and Feynman diagrams, requiring new techniques such as gauge-gravity correspondence. The latter is also known as holography, because it is based on the description of a strongly interacting quantum field theory in flat spacetime as sort of a hologram in a higher-dimensional curved spacetime.

A theoretically clean and well studied example of gauge-gravity duality is the so-called AdS/CFT correspondence, where the higher dimensional spacetime is a maximally symmetric negatively curved (anti de Sitter) space and the quantum field theory in one dimension less is a conformal field theory (CFT). Conformal field theories also play important roles in string theory (see below).

- Highlight: Our involvement in the muon g-2 (in German)

Gravitation

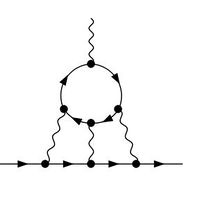

Since the groundbreaking work of Einstein, gravitation is conceived as defining the geometry of spacetime - even defining the very concepts of time and space itself. Planetary motion as well as the motion of massless particles, that is to say light, become the straightest possible paths in a non-Euclidean geometry.

Fig.: Light-cone of an event representing its causal past and future.

General relativity is a very successful theory. Its predictions range from the deflection of light by massive bodies which distort spacetime (Einstein-lensing) to that of gravitational radiation carrying away energy in the form of "ripples" in spacetime (Hulse-Taylor binary pulsar), as well as to the expansion of the universe (microwave background radiation). One of the most spectacular predictions of general relativity is the existence of black holes, which by now has been confirmed indirectly by numerous astrophysical observations.

Despite of these successes there are several unresolved problems in the physics of gravitation, some of which are considered as the biggest problems in contemporary theoretical physics:

- The cosmological constant problem entails a gigantic discrepancy (123 orders of magnitude) between observation and naive theoretical expectation, and so far no satisfying explanation exists that resolves this discrepancy.

- Numerous astrophysical and cosmological observations reveal discrepancies with the theory of general relativity, unless we postulate the existence of dark matter, which so far has not been detected in particle physics experiments.

- The elusive theory of quantum gravity still is very much a theory under construction, with several conceptual and technical issues seeking for solutions.

- General relativity predicts its own failure as a consequence of the famous singularity theorems. Physically this means that spacetime contains regions where the curvature grows without a bound. The most prominent examples are the singularities within black holes as well as the Big Bang singularity.

Deeper insights into the structure of physical systems have often been achieved by the imposition of symmetries. This usually breaks the problem down into simpler building blocks which ideally allow a complete solution. Gravity is no exception to this rule since the prototypic black-hole solution, the Schwarzschild geometry (actually the first exact non-trivial solution of the Einstein-equations), has been found precisely along theses lines, i.e. upon imposing spherical symmetry. It is therefore natural to pursue a similar plan of attack for the quantization of gravity. The corresponding models become gravitational theories in a 1+1 dimensional spacetime coupled to the area of the two-sphere which becomes a dynamical variable in the reduced theory. There are several other ways how lowerdimensional (1+1 and 2+1) models arise from higherdimensional configurations in string theory or general relativity, and the description of gravity in lower dimensions is one of the key research fields of our group.

Quark-Gluon plasma

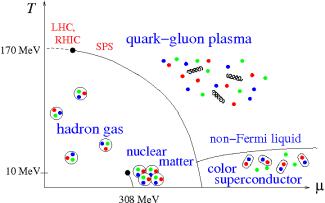

Quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the accepted theory of the strong interactions responsible for the binding of quarks into hadrons such as protons and neutrons, and the binding of protons and neutrons into atomic nuclei. The fundamental particles of QCD, the quarks and gluons, carry a new form of charge, which is called color because of its triplet nature in the case of the quarks (e.g. red, green, blue); gluons come in eight different colors which are composites of color and anticolor charges. However, quarks and gluons have never been observed as free particles. Nevertheless, because quarks have also electrical charge, they can literally be seen as constituents of hadrons by deep inelastic scattering using virtual photons. The higher the energy of the probing photon, the more do the quarks appear as particles propagating freely within a hadron. This feature is called "asymptotic freedom". It arises from so-called nonabelian gauge field dynamics, with gluons being the excitations of the nonabelian gauge fields similarly to photons being the excitations of the electromagnetic fields, except that gluons also carry color charges. Asymptotic freedom is well understood, and the Nobel prize was awarded to its main discoverers Gross, Politzer, and Wilczek in 2004.

Much less understood is the phenomenon of "confinement", which means that only color-neutral bound states of quarks and gluons can be observed. This confinement can be overcome when the temperature is very large, as, for example, in the first instances of the Early Universe. In this case, quarks and gluons form a quantum fluid that is known as the quark-gluon plasma. Its unique properties are studied on Earth in large collider facilities at LHC (CERN, Switzerland) or at RHIC (BNL, United States), where this plasma is created in ultrarelativistic heavy-ion collision experiments.

Fig.: Qualitative sketch of the expected phase diagram of quark-gluon matter as a function of temperature T and quark chemical potential µ. Solid lines denote first-order phase transitions, the dashed line a rapid crossover.

In our group, we investigate different thermal and nonthermal properties of the quark-gluon plasma, putting particular emphasis on its non-equilibrium early-time evolution shortly after the heavy-ion collision. Using a variety of different techniques, involving perturbative calculations, kinetic theory, hydrodynamics, holography, real-time lattice simulations and artificial neural networks, not only enables us to extract dynamical and universal key features of the plasma, but also to link to other fields of research like machine learning, gravity, the Early Universe and experiments with ultra-cold Bose gases.

String theory

The names of the fundamental forces are related to their strength. The strong force is much stronger than electromagnetism and is thus able to overcome the repulsive force between objects with the same electrical charge (protons or quarks). The weak force is weaker than electromagnetism but still much stronger than gravity. The reason that we almost only recognize gravity in everyday life is that the macroscopic objects are neutral. They don't carry an effective color charge and they carry - if at all - only very small electric charges. For gravity there is no negative charge (negative mass), so that all the small gravitational effects add up to something which is strong enough to move galaxies and build black holes. The seperate description of the forces is quite accurate by now. This is summarized in the standard model of particle physics.

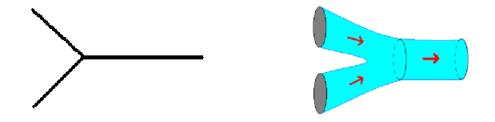

A measure for the strength of a force are the coupling constants of the corresponding theory. They are, however, not constant, but depend on the energy level one is dealing with. If one extrapolates their values to high energies, one discovers that the couplings of electromagnetism, strong and weak force meet at a certain energy level almost in one single point (see Figure 1). This supports the idea that those three forces could be just different aspects of one and the same universal force. There are several theories which try to describe this unification. They are called GUTs, 'grand unified theories'. However, to be really 'grand', such a unification should also include gravity, whose coupling constant is far weaker still at this high energies. The theory, which will manage to unify all forces, including gravity, is sometimes called TOE, "theory of everything". String theory is one candidate, and at present actually the only one for this TOE.

Fig.: Left: Point particle interaction, Right: Closed string interaction, note the smooth interaction surface.

'SUSY' stands for supersymmetry and means that there is an exchange symmetry between fermionic particles (like quarks and electrons) and bosonic ones (like photons and even gravitons, if one includes gravity into the considerations). It does, however, not relate the already known particles, but it predicts new supersymmetric partners to the known particles (called e.g. squarks, selectrons, photinos and gravitinos). So far none of those superparticles has been discovered, but there are a lot of theoretical reasons for believing in supersymmetry. Supersymmetry is an integral part of string theory, or more precisely 'superstring theory'. If supersymmetry is realized at energies not too far above the scale of electroweak symmetry breaking, the Large Hadron Collider at CERN may be able to discover its signatures in its ongoing searches of physics beyond the standard model.